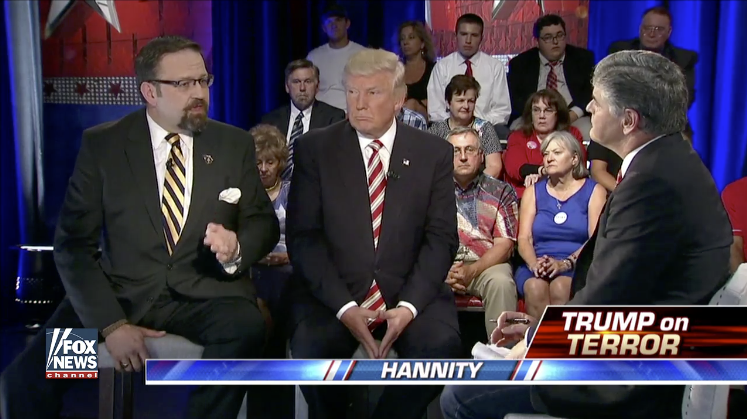

Before Sebastian Gorka was an adviser to President Donald Trump, he was a man with a dream to rise to the top of Hungarian politics. It didn’t quite work out.

Gorka, a deputy assistant to the president who focuses on counterterrorism, was denied security clearance in 2002 to serve on a committee investigating the then-Hungarian prime minister’s past as a communist secret police official during Soviet times. That denial, local security officials and politicians told BuzzFeed News, effectively ended his career as a national security expert in Hungary.

Washington’s standards may be lower than Budapest’s. Gorka has been widely criticised for his lack of qualifications and connections with fringe political groups since joining the Trump administration. In the past few months, his ties with far-right Hungarian groups and past as an editor at Breitbart News have raised questions about both his ideological views and his judgment. But, back in Hungary in the 2000s, he wasn’t seen as an extremist, but instead a self-promoter, who exaggerated claims about his past, including his work for the British intelligence services.

“Sebastian Gorka is not a Nazi or a security threat because he is some sort of secret British agent,” said a member of the Hungarian counter intelligence service, who has reviewed the files a security background check on Gorka from 2002. “Gorka is, how do you say in English — a peddler of snake oil.”

The White House press office did not respond to several phone calls and emails seeking comment. BuzzFeed News made two calls to Gorka’s mobile and sent three text messages, none of which were answered.

Gorka’s rise offers a glimpse at how permeable the top strata of American power is in the age of Trump. It seems to be easier to rise in the Trump White House than it was in the newly free Hungarian government at the turn of the century. The Trump administration is full of figures like Gorka, plausible TV talking heads with no particular expertise. His wafer-thin counterterrorism résumé, associations with the political fringes in Hungary, and questions about the depth of his experience are a particularly vivid illustration of what it takes to get the ear of a president famous for adopting the view of the last person with whom he spoke.

Gorka, born in 1970 in the UK to Hungarian parents, immigrated to Hungary in the early 1990s after graduating from Heythrop College at the University of London with a degree in philosophy and theology. While the exact timeline of his activities in Hungary remains opaque, Gorka joined a flood of expats heading for Hungary after the collapse of the Communist regime in 1989. He embarked on a career as a national security expert, working as a low-level staffer at the defense ministry, attempting to form defense-based think tanks and working as a minor pundit. But the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, appear to have been a turning point — after which he tried to rebrand himself as an expert on „Islamic terrorism.” He then made a final attempt at a career in politics in Hungary, but was soundly beaten in a local election race, failing to become mayor of a small Hungarian town in 2006. Within two years, he immigrated to the US. From there it was onwards and upwards to the White House.

It was in 2002 when Gorka tried to make a real mark in the Hungarian national security world. Then-prime minister Péter Medgyessy was suspected of having worked as a secret police officer in the Communist era, and Gorka wanted to join a parliamentary committee that was investigating him.

But Gorka was rejected for security clearance within weeks by Hungarian counterintelligence, who cited his repeated claims of contact with British intelligence as a security risk, according to a former Hungarian foreign minister and an intelligence agent familiar with his file.

In trying to build his reputation as a defense and intelligence expert in Hungary, Gorka had relied on his history as a member of a reservist UK army intelligence unit, a role he claims to have held for three years, from about 1989 to 1992. The UK Ministry of Defence would not return requests for confirmation on the exact period and nature of Gorka’s service.

According to the Hungarian intelligence agent, Gorka used this short military career — in what was a volunteer force, known as the 22 Intelligence Company of the Territorial Army — as a jumping-off point to claim security expertise in intelligence collection and counterterrorism. He would have been unlikely to directly work in these two fields during his short time as a reservist, according to a former British military intelligence officer, who described the program at the time as a “bit of a joke.”

“The 22 Intelligence was a Cold War-era reservist unit that was developed to recruit people with language skills useful in the Cold War era,” said the former officer, who requested anonymity as they continue to work with the UK defence ministry. “I have seen Gorka claim that he had experience with Northern Ireland in this period but … that unit was focused on putting together teams that could help with translations in central or eastern Europe in the case of a Cold War crisis.”

Gorka promoted these claims of ties to UK intelligence in public and private conversations through the turn of the century, according to multiple sources who spoke with him during this era. They gave him some credibility with the Hungarian national security field at first, as Hungary continued to dig its way out of nearly five decades of Communist rule, but it eventually backfired and cost him a chance to officially serve in a larger national security capability.

The intelligence community concluded, according to the Hungarian agent, that he was exaggerating the extent of his ties to the British intelligence services.

The intelligence officer — who cannot be publicly named because he lacks government approval to discuss the matter — told BuzzFeed News that the intelligence community believed that Gorka probably did maintain some ties to British intelligence after his arrival in Hungary. But he also said that Gorka openly bragged about being an agent for MI6 — the British Secret Intelligence Service — throughout the 1990s, according to multiple people familiar with him during this era. There is no evidence that Gorka was a member of MI6.

The intelligence officer said the investigation for his security clearance did not believe Gorka was being candid. “These claims were not considered credible because by this point we understood that Gorka and many like him didn’t return to Hungary because of patriotism or skills but rather because they couldn’t be successful in the West, where they were born or raised, and thus wanted to come to Hungary,” the officer said. “So do we believe that he was an MI6 agent like he claimed? No, he’s not smart enough or well-trained enough.” The officer said that whatever the reality of his experience with the British Army was, it “was enough for most Hungarians to think he shouldn’t be trusted as a national security official.”

Gorka’s rejection for a security clearance to serve on the committee was a devastating blow to his reputation in Hungary. He had come to be seen as a self-promoter, the intelligence official said, while the minor ties to the British government that had been established were enough to alienate him from much of the Hungarian nationalist right.

The early ‘90s were a great time for returning expats to get jobs in the now formerly Communist Hungary as expertise in the West was highly valued at the time, and Gorka was keen to make the most of the opportunity.

It was Geza Jeszenszky, former foreign minister of Hungary and a former ambassador to the United States, who thinks he gave Gorka his first job with the Hungarian government.

“I can’t recall the first time I met Sebastian Gorka, but by the early 1990s, he was working for the Ministry of Defense here in a minor capacity,” Jeszenszky told BuzzFeed News during an interview in his antique-filled apartment in central Budapest. “At that time we needed people who had been trained in the West because so many of our officers had been trained by the Soviets and we were going to need expertise to integrate our military with NATO.”

“I had known his father briefly, and if someone finds evidence it was on my recommendation, I wouldn’t dispute it,” he said. “A young man born in Britain, born to a Hungarian nationalist, who wants to return home and serve Hungary? This all would have sounded very well to me at the time.”

It didn’t always work out as planned. “Some people turned out not to be usable,” Jeszenszky said.

According to Gabor Horvath, editor of a newspaper called Népszava, “anyone coming from the West during this time could get a government job based on this idea that Hungarians who’d grown up in the West were somehow more intelligent and better educated.”

Gorka moved to Hungary in his early twenties. His father, Paul Gorka, had become a renowned figure in Hungarian expat circles after he was convicted for working as a British spy in the 1950s. He was jailed and tortured by Hungary’s Communist regime and eventually immigrated to the UK after the 1956 uprising against the Soviet Union.

In his fight against the Communist regime, Gorka’s father would have had to make difficult compromises of the kind made by people across Central and Eastern Europe in the bloody 20th century. Facing down the Soviet Union was not a simple case of good against evil, and would have entailed lining up alongside unsavory figures who emerged from the Nazi era of the ‘30s and ‘40s, and whose anti-Semitic views persist to the current day.

In 1979, the elder Gorka was given an award by a Hungarian veterans group to honor his service in the 1956 uprising. The Order of Vitéz, known in Hungarian as Vitézi Rend, was first issued by the Hungarian dictatorship in 1920 to commemorate heroism during World War I, but was discontinued in 1944, having become a symbol of Nazism. The order was revived in the 1970s by a number of different Hungarian nationalist groups and veterans associations, who said they wanted to reclaim it as an award for patriotism.

That came back to haunt the younger Gorka after he was pictured attending Trump’s inaugural ball on Jan. 20 wearing the Order of Vitéz medal. Two months later, The Forward reported that Gorka had sworn allegiance to the group, citing leaders of the organization. That, in turn, prompted calls by some senators and Jewish groups to investigate Gorka, some going so far as to call for his dismissal. This week, the The Forward reported that Gorka’s alleged ties to the group — which he has denied — in fact go back decades. The revelations brought a new wave of controversy. Some of Gorka’s critics have labeled him a Nazi sympathizer, although Gorka and his supporters say he was merely paying homage to his father, an ardent anti-Communist.

Gorka denied being affiliated with the Order in an interview with Tablet, and further rejected charges of anti-Semitism in a panel discussion at Georgetown University on Monday, telling protesters at the scene: “Every young person holding a placard to protest my parents and myself — I challenge you now: Go away and look at everything I have said and written in the last 46 years of my life and find one sentence that is anti-Semitic,” he said, according to NBC. „You won’t find one.”

This chimes with the views of some of those who knew him in Hungary, who remember Gorka as right-wing and keenly pro-Western, but whose views set him outside the far-right.

Tamas Molnar formed a political party with Gorka called the New Democratic Coalition after meeting him in 2006 during a series of anti-government demonstrations. The idea, Molnar said, was to challenge both the ruling Fidesz Party and the ultra-right-wing Jobbik Party.

Molnar, who retired in 2008 from a 30-year political career, now lives on an island about 20 miles outside Budapest, where he works on Hungarian pagan revival art and tends a small vineyard.

In remembering his political discussions with Gorka between 2006 and 2008, Molnar described someone with hard-right ideological views but also a belief in liberal democracy: “In the case of Gorka, he continued to criticize both Jobbik and Fidesz for their reluctance to embrace the West and their eventual turn back toward Putin’s Russia.”

“He was always clear the future of Hungary lay with the West and that Putin was just an extension of the Soviet totalitarian regime,” he said.

Horvath, the editor, took a similar view — that it was too simple to label Gorka a far-right extremist: “Within the context of historical Hungarian fascism, Gorka never appeared to be particularly interested in these [extreme, Nazi-linked] movements, having always been a supporter of the pro-Western Atlantic alliances and an advocate for Hungarian integration into the West,” he said. “So I don’t think it’s fair to characterize him as a Nazi, when he’s more of a self-promoter.”

Horvath described the Hungarian far-right as a rich and diverse historical tapestry of fascist thought that throughout the first half of the 20th century dominated Hungarian politics and set the stage for the current authoritarian government led by Prime Minister Viktor Orban and his Fidesz Party.

“The charges that Gorka supports anti-Semitic movements” — such as Jobbik, which has been roundly criticized by human rights groups across Europe — „doesn’t seem consistent with his attitude or background when he was here in Hungary,” said Horvath, citing Gorka’s loud pro-Western stance. “While all anti-Semites seem to be Nazis, not everyone in the Hungarian right is a racist because there’s a lot of diversity in thought.”

When asked about the controversy over Gorka’s use of his father’s Order of Vitéz medals and title, Molnar first dismissed the complaint, arguing that the Order was fairly common in Hungarian political circles, and is associated with nationalism rather than ideology.

But given Hungary’s history as a fascist state in the 1920s, and early embrace of Hitler, Molnar admitted that a public display of the Order could now be seen to have anti-Semitic undertones.

“Yes, I will admit that it would be seen as anti-Semitic by Jews familiar with Hungarian history,” he said. “But that was never its intent.”

Akos Stiller for BuzzFeed News

Corvinus University in Budapest.

Gorka spent much of his time in Hungary focusing on lobbying donors for financial backing for a series of institutes and think tanks, according to Horvath, Jeszenszky, and others who knew him at the time.

Horvath remembers first meeting Gorka at a 2006 fundraiser at the Hudson Institute, a think tank in Washington, DC, when Horvath was working in the US as a foreign correspondent.

“It was a fundraiser for a think tank or institute he was trying to establish with his wife,” he said. “Of course I knew of him as a fringe member of the Hungarian national security establishment but remember thinking to myself that it was odd he was promoting his so-called expertise on Islamic radicalism, because the Hungarian educational system isn’t exactly a hotbed of counterterrorism scholarship.”

Gorka got his PhD in 2007 from Corvinus University in Budapest. His dissertation on terrorism theory has since been widely criticized by experts in international terrorism for its vagueness and superficiality.

Daniel Nexon, an associate professor of International Security at Georgetown University, wrote in a series of blog posts that the dissertation would not have been accepted in an American undergraduate program. “I would not characterize it as a work of scholarship,” Nexon wrote. “I am confident that it would not earn him a doctorate at any reputable academic department in the United States. Indeed, it would be unacceptable as an undergraduate thesis for the Department of Government or the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. My guess is that Gorka wanted to call himself ‘Doctor,’ and his PhD-granting institution was happy to oblige.”

Now Gorka works in the White House as an adviser on counterterrorism, but as recently as March, he had reportedly yet to receive a security clearance. The White House did not respond to a request for comment on whether Gorka had received his clearance.

“The last I heard he had not been cleared to sit in any sort of national security meetings, which leaves him without much to do all day,” one former Obama administration defense official said in early April. The official remains in contact with the professional staff at the National Security Council and asked for anonymity to openly discuss off-the-record conversations with former colleagues.

“It was never clear what his qualifications were for any sort of posting,” the official said. “But without that clearance he’s not allowed to sit in the real meetings or review intelligence. I am told he basically sits in the White House canteen drinking coffee between Fox News live hits.”

Gorka’s ability to parlay a failed career as a national security expert and local politician in Hungary into a position at the White House advising the president of the United States on national security matters amuses Horvath.

“I admit some Hungarians are asking questions about how someone who failed here could end up in the White House,” he joked. “It doesn’t look good for America.”